In the bustling markets of Lagos, the vibrant streets of Nairobi, and the creative hubs of Johannesburg, a quiet revolution is taking place. Across Sub-Saharan Africa, a new generation of designers and brands is redefining what it means to embrace "ethnic" or "tribal" fashion. Gone are the days when African prints were merely exoticized or reduced to clichés for Western consumption. Today, these brands are weaving contemporary narratives with deep cultural roots, creating a fresh aesthetic language that speaks to both local pride and global appeal.

At the heart of this movement is a deliberate shift away from the term "ethnic" itself—a label often laden with colonial baggage. For decades, African textiles like Dutch wax prints (ironically of Indonesian origin) were marketed as "authentic" African attire, despite their complicated transnational history. Now, designers are reclaiming narratives by spotlighting genuinely indigenous techniques: Bogolan mud cloth from Mali, Adire tie-dye from Nigeria, or Kente weaving from Ghana. These aren’t just fabrics; they’re carriers of ancestral knowledge, with patterns that encode proverbs, social status, and even historical events.

The rise of homegrown labels like Nigeria’s Orange Culture or South Africa’s MaXhosa by Laduma exemplifies this renaissance. These brands refuse to be pigeonholed as "ethnic" designers. Instead, they blend traditional motifs with razor-sharp tailoring, streetwear silhouettes, or gender-fluid designs. A MaXhosa knitwear piece might reinterpret Xhosa beadwork patterns into a modern sweater, while Orange Culture infuses Yoruba adire with Tokyo-inspired oversized cuts. The result? Garments that feel simultaneously timeless and avant-garde—worn as easily on Brooklyn rooftops as at Dakar fashion weeks.

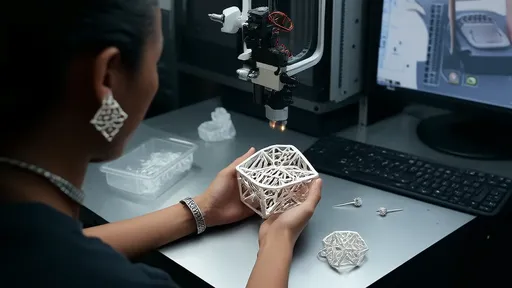

What’s particularly striking is how these brands engage with sustainability—not as a trendy add-on but as intrinsic to their ethos. In Ethiopia, Paradox employs centuries-old hand-spinning methods to create zero-waste designs. Rwandan label Uzuri K&Y transforms recycled flip-flops into high-end sandals, collaborating with local artisans. This isn’t just eco-consciousness; it’s a quiet subversion of fast fashion’s exploitation, proving that ethical production can coexist with jaw-dropping aesthetics.

Social media has turbocharged this movement. Instagram accounts like @theafricandesigner or @afrikafashionweek serve as digital runways, bypassing traditional gatekeepers. When Beyoncé wore a custom Burberry cape featuring Basotho blankets in her Black Is King visual album, it wasn’t just a celebrity endorsement—it signaled how African designers now set trends rather than follow them. Younger consumers, both on the continent and in the diaspora, increasingly demand fashion that reflects their hybrid identities: a Lagos influencer might pair a Tokyo James leather harness with vintage kente, while a Nairobi art curator layers a Studio 189 batique dress over distressed jeans.

Yet challenges persist. Piracy remains rampant, with international fast-fashion chains copying African prints without credit or compensation. Infrastructure gaps mean limited access to high-quality textiles, forcing some designers to import materials at steep costs. And the "ethnic" label still looms—buyers often expect "African fashion" to fit a narrow aesthetic box of bold prints and earthy tones, leaving little room for experimentation with monochromes or tech fabrics.

Perhaps the most profound shift is psychological. For decades, wearing traditional attire in urban African settings was sometimes dismissed as "village" or backward. Now, when a banker in Abidjan dips a suit lapel in Baule cloth, or a Gen-Z crowd in Accra mixes Fante kaba sleeves with bike shorts, it’s a political statement—a rejection of Western sartorial dominance. As Senegalese designer Selly Raby Kane puts it: "We’re not exotic. We’re the new normal."

The numbers tell their own story. According to the African Development Bank, the continent’s textile industry could generate up to $15.5 billion annually within a decade. Luxury e-tailers like ALÁRA or Industrie Africa now ship African designer pieces worldwide, while Lagos Fashion Week has become a mandatory stop for international editors. This isn’t a fleeting trend; it’s the birth of a parallel fashion ecosystem where the rules are written in Bamako rather than Paris.

So what does "ethnic fashion" mean in this context? Perhaps nothing at all. When a Congolese sapeur layers a Kitenge waistcoat over a Dior shirt, or a South African punk artist shreds a Shweshwe-print jacket, they’re not performing ethnicity—they’re dismantling the very concept. In Sub-Saharan Africa’s creative crucible, tradition isn’t preserved under glass; it’s remixed, hacked, and reborn daily. And that, more than any label, is true innovation.

By /Jun 25, 2025

By /Jun 25, 2025

By /Jun 25, 2025

By /Jun 25, 2025

By /Jun 25, 2025

By /Jun 25, 2025

By /Jun 25, 2025

By /Jun 25, 2025

By /Jun 25, 2025

By /Jun 25, 2025

By /Jun 25, 2025

By /Jun 25, 2025

By /Jun 25, 2025

By /Jun 25, 2025

By /Jun 25, 2025

By /Jun 25, 2025

By /Jun 25, 2025